Patching the pouch

- Other Tobacco Products Print Edition

- July 1, 2017

- 0

- 1

- 10 minutes read

By reducing snus’ notorious sting, a Swedish inventor wants to make it easier for smokers to go smokeless.

By Taco Tuinstra

Bengt Wiberg was devastated. He had just been diagnosed with a third-degree lesion, and the dentist blamed snus. The only way to restore oral health, his dentist insisted, was to quit smokeless tobacco.

“It was the worst day of my life,” says Wiberg.

A snus aficionado and former smoker, Wiberg did not want to stop snusing—and he certainly did not want to revert to smoking. The pain was so intense, however, that he could not even stand to hold snus in his mouth. So, back in his office, Wiberg started pondering his predicament.

The cause of his oral discomfort was clear: Snus has a high pH level, which assists nicotine uptake and delivery time but can also irritate the gum and oral mucus membrane. If the snus is pressed against the same spot of the mouth for a prolonged period—like snusers tend to do—it can cause a lesion. The affected area becomes extremely sensitive, and the spicy juices released by snus can sting like salt in a wound.

That analogy gave Wiberg an idea. “What do you do when you cut your hand?” he asks. “You put on a Band-Aid to keep out the dirt and sweat.” So, he took one from his employer’s first-aid kit, patched one side of a snus pouch and cut away the excess material. He then stuck the pouch in his mouth with the patched side facing his gums. “The pain disappeared immediately,” he says.

Remarkably, the flavor and nicotine absorption were unaffected by his improvised patch. Because nicotine is water soluble and absorbed by all the mouth’s mucous membranes, the snusing experience was as satisfying as before—but without the discomfort.

Wiberg continued snusing, experimenting with different patch materials, such as surgical tapes. After a year, he returned to his dentist, who was astonished to find no evidence of gum or mucosa irritation. Despite Wiberg’s ongoing snus use, the lesion had disappeared, and the color of his gums had changed from swollen red to healthy pink. “My oral health was excellent,” beams Wiberg.

Getting started

Convinced that other snusers might benefit from his experience, Wiberg composed a long message to Swedish Match, the world’s largest snus manufacturer. He described his solution in detail, along with the market potential, but just as he was about to click “send,” he stopped himself.

Instead of giving away his idea, he contacted Start-Up Stockholm, a Swedish government-financed nonprofit consultancy for entrepreneurs in the startup and early growth stages of their ventures. Start-Up Stockholm helped secure a sek20,000 ($2,300) government grant to get started. “I am probably the only person in Swedish history to receive government money for a tobacco-related invention,” Wiberg says with a grin.

After due diligence revealed that nobody had claimed credit for a similar technology, Wiberg filed for patent protection in Sweden and, later, in the United States and at the European Patent Office. Sweden granted the patent in early 2017, and Wiberg is confident that the other jurisdictions will follow suit. “My country is quite fussy when it comes to recognizing patent applications,” he notes.

In the meantime, Wiberg kept perfecting his solution. After trying many different patch materials, Wiberg settled on an impermeable, soft and ultrathin (0.025–0.035 mm) membrane that has been approved by Sweden’s national food agency. Harmless and unnoticeable for the snus user, the material also complies with all applicable EU regulations.

In June 2016, Aftonbladet, a leading Swedish newspaper, published a big story about Wiberg’s invention. With 600,000 unique impressions, it became the paper’s most read article that day. In December 2016, the Venture Cup recognized the innovation, labeled “Sting Free Snus,” as one of the best business ideas in Sweden that year.

Harm reduction

While the patch can help prevent oral discomfort for existing snusers, Wiberg believes its real value lies in removing a hurdle to the adoption of snus by cigarette smokers. Snus has already proved to be an effective stop-smoking aid, delivering the enjoyment of nicotine without the disease-causing byproducts of combustion (snus is estimated to be up to 99 percent less unhealthy than smoking). A study by L.M. Ramstrom and J. Foulds revealed that more than 70 percent of snus users in Sweden were former cigarette smokers who had quit smoking permanently.

Wiberg suspects that snus could help even more people quit smoking if it wasn’t for the product’s characteristic sting, which he compares to the “pins and needles” sensation a person may feel after his foot has fallen asleep. This sting is experienced not only by users with compromised mucus membranes but also by the typical, healthy user (the “injured” users just experience it worse). In a consumer survey conducted by Wiberg, four out of 10 respondents said they found the sting unpleasant. A minority considered the sting an attractive feature in the way that some diners enjoy the “pain” associated with spicy foods, while others were indifferent. By dulling the snus sting, Wiberg’s solution could therefore contribute to public health.

The inventor is now working on the commercialization of his creation. Swedish Match has signed up for a nonexclusive licensing agreement for the rights to utilize Sting Free Snus technology for its products. That leaves Wiberg the options to start his own manufacturing operations, contract more licensees or sell the patent to a third party.

According to Wiberg, Sting Free Snus is an attractive business proposition. Incorporating his membrane, he says, adds little to the cost of production, but snus companies would be able to charge a premium for the sting-free varieties of their brands. Tobacco retailers stand to benefit, too. Even if increased snus sales would come at the expense of cigarette sales, they would still gain because retail profit margins (in Sweden, anyway) are almost 100 percent higher for snus than those of cigarettes.

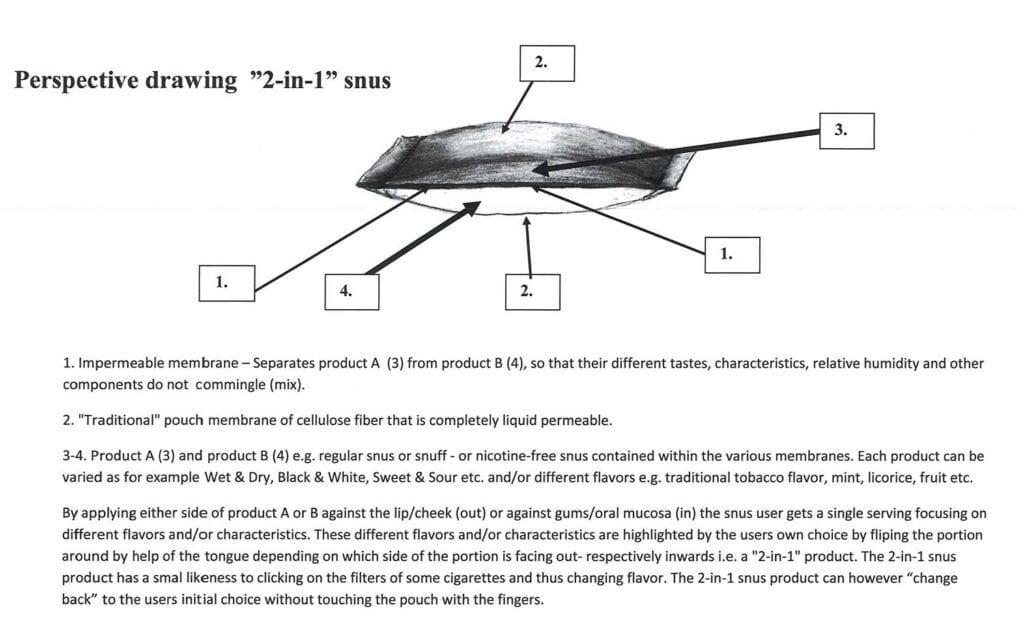

The patch also creates opportunities for new, innovative products. A separate patent covers a two-in-one pouch, with two flavors separated by an impermeable membrane. Depending on his preferences, the user can flip the pouch with his tongue so that the desired flavor faces the lip (snus users taste their snus by striking their tongue over the front-facing side of snus pouch). Wiberg compares it to the popular crushable filter capsules that allow smokers to flavor their cigarette smoke. But whereas the crushable-capsule concept is irreversible—once crushed, there is no way of returning to the original flavor—the two-in-one snus pouch allows the user to keep switching flavors indefinitely. “For example, you can enjoy whiskey flavor and then quickly switch to strong mint before kissing your wife,” he says.

For the time being, the snus market is limited primarily to Scandinavia ($1 billion in annual sales) and the United States. Snus is banned in all EU member states except Sweden, but that may be about to change. The European Court of Justice is set to review a challenge brought by Swedish Match and others, and experts are cautiously optimistic that it will throw out the ban. If that happens, it could make snus available to more than 100 million smokers.

China, too, has approved snus. According to Wiberg, the China National Tobacco Corp. recently launched two flavors: “Black Tea” and “Deep Frozen.” China, of course, is the largest cigarette market in the world. If only a fraction of the country’s 350 million smokers converted to snus, the gains for public health—and snus sellers—would already be immense. And they would be even greater if Chinese smokers would have access to a non-stinging snus variety.

Snus lovers around the world have responded enthusiastically to Wiberg’s invention, describing it as a milestone. Retailers in Sweden report frequent inquiries about the product, which has not even been launched yet. But perhaps the biggest endorsement came from Curt Enzell, a professor of organic chemistry, a retired Swedish Match R&D director and the father of the snus pouch.

Tired of washing from his fingers the brown stains associated with loose snus, Enzell in 1967 placed his snus into an empty tea bag and thus inspired the creation of an entirely new product category. Portioned snus is still regarded as the most significant breakthrough in snus, as it has made the product more user-friendly and increased its consumer base. After evaluating Wiberg’s product, Enzell declared Sting Free Snus the greatest innovation relating to the snus portion since his pouch.